The word data is usually used to refer to numerical data, statistics and other types of (usually electronic and quantitative) information (Upton and Cook, 2014). With reference to migration, it is important to be clear on the different meanings of data and statistics.

The term “migration data” refers to “all types of data that would support the development of comprehensive, coherent and forward-looking migration policies and programming, as well as contribute to informed public discourse on migration. This includes data concerning different forms of population movement, including short and long-term, forced and voluntary, cross-border and internal, as well as data concerning characteristics of movement and those on the move, reasons for and impacts of migration”. Migration data also include relevant data relating to migrants and migration from related policy sectors, such as the labour market, health and education.

IOM, 2021.

The science of collecting, displaying, and analysing data.

Upton and Cook, 2014.

When migration data are collected, checked and organized using statistical methods, they become known as “migration statistics”. Data for policymaking on migration are generated in a variety of ways and using different methodologies. They concern everything, including:

- basic statistics on migration, such as stocks of migrants (how many migrants live in different countries) and flows of migrants (the size and direction of inflows and outflows of migrants);

- the characteristics of migrant populations (such as their demographic profile, education or qualifications);

- information on different migration topics (such as migration and gender, migration health, migrant integration, labour migration or human trafficking);

- information on other relevant sectors (characteristics of the labour market, education system, immigration policies, health services, etc).

Broadly speaking, these data fall into two main categories: quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative data consist of numerical and quantifiable evidence on migration. Quantitative data help understand the incidence and rate at which a phenomenon is occurring, showing trends and enabling the making of projections.Qualitative data are descriptive and collected using techniques such as interviews or focus groups. Qualitative data help to understand why a phenomenon might be occurring and the different perceptions and factors that influence it.

The United Nations Statistics Division, under the guidance of the United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, developed a conceptual frameworks and concepts and definitions on international migration, which sets out guidance on migration data for countries to follow. These recommendations establish concepts and definitions related to the measurement of international migration and provide the best basis for collecting reliable and internationally comparable migration statistics.

The core concepts of migration data used internationally are based on a substantial revision of the United Nation’s 1998 Recommendations on Statistics of International Migration. The new conceptual framework includes concepts of mobility as well as migration, and was developed with key policy interests in mind. It seeks to align methods of measurement for international migrant populations with those for resident populations, and to achieve coherence between flow and stock data across countries by harmonising concepts for four key population sub-groups; foreign-born, native-born, foreign citizen and national citizen. It also seeks to address the demand and challenges related to data on international temporary mobility. Key concepts introduced in the revision by the United Nations Group of Experts (2020) include:

Immigrant population stocks include all persons who reside in the country who are either born in another country or who do not hold national citizenship, including stateless persons at a given point in time. Emigrant population stocks include all national citizens or persons who were born in the country and are residing in another country at a given point in time. (See also the Migration Data Portal for further details on stocks).

Note: Persons who are born in the country and have national citizenship are not considered part of the immigrant population, although they can be considered (recent) immigrants or part of the immigration flow if they returned and changed their country of residence.

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

Migration flows data capture the number of migrants entering and leaving a country over the course of a specific period, such as one year [United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) Statistics Division, 2017a]. Immigration flow includes all persons entering the country and becoming part of the resident population within a given year, including persons with national or foreign citizenships or stateless persons, while emigration flow includes all persons leaving the country to become a part of another country`s resident population within a given year, including persons with national or foreign citizenships or stateless persons.

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

Note: See also the Migration Data Portal for further details on flows.

all movements that cross international borders within a given year.

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

all movements resulting in a change in the country of residence (a subset of international mobility) within a given year.

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

a person who has changed his or her country of residence and established new residence in the country within a given year. International migrant can be either ‘immigrant’ or ‘emigrant’ and include those with national or foreign citizenships or stateless persons.

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

individuals who either (a) have lived most of the last 12 months within a given year or have intentions to stay (or granted to stay) for at least 6 months; or (b) have lived at least 12 months within a given year or intentions to stay (or granted to stay) for at least 12 months, not including temporary absence for holidays or work assignments (UN DESA Statistics Division, 2017a).

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

all persons who were present in the country at a specific reference moment (census reference moment); includes residents who were present in the country but excludes residents who were not present at the reference moment (UN DESA Statistics Division, 2017a).

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

all persons who stayed or intend to stay (or granted to stay) in the country for less than minimum duration required for residency in a particular year.

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

all movements that cross international border that do not result in a change in the country of residence.

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

all persons who are not residents of the country of measurement but have been engaged in economic activities on a repeated basis (more than once in a year) in that country provided they depart at regular and short intervals (daily or weekly) from the country [International Labour Organization (ILO), 2018].

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

all persons who are not residents of the country of employment, whose work by its character is dependent on seasonal conditions and is performed during part of the year (ILO, 2018). Other types of temporary workers include all persons who are not residents of the country of measurement but travel to the country for short periods (less than the minimum duration requirement for residence) for work-related reasons, such as itinerant workers and project-tied workers).

United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 2020.

Through the application of common concepts and definitions, international trends can be identified and compared. However, despite UNSD efforts to promote the use of standard definitions, migration data are still collected in many different ways, often using a variety of definitions. For instance, the length of time a person needs to be abroad to be considered a migrant (and not a tourist), varies from country to country. Similarly, the duration of permits for the same type of migration movements may also vary.

When studying national data, it is therefore important to understand the concepts and definitions used in national data and how these may differ from the international recommendations.

- The United Nations Population Division provides a description of different types of empirical data, estimates and indicators.

- The Migration Data Portal by GMDAC (of IOM) presents and provides a detailed description of different types of migration data.

- The Global Migration Group (GMG) has also prepared the Handbook for Improving the Production and Use of Migration Data for Development (2017) on the relative strengths and limitations of different sources.

- IOM, Migration and migrants: A global overview, 2019 (Chapter 2, World Migration Report 2020). Discusses not only the latest numbers but also challenges in collecting data and data gaps.

At the international level, several organizations and bodies, including UNSD, have established guidance on migration statistics. These include guidance for countries on national statistics collection (for example, recommendations for using specific statistical instruments, such as censuses and surveys, as per Policy approaches box below) as well as guidance on how to address global needs for migration data, such as those related to the 2030 Agenda.

- Use internationally agreed concepts and definitions.

- Ensure all core questions on migration recommended by the United Nations are included in all censuses and surveys (see Principles and recommendations for population and housing censuses, revision 3).

- Include questions on country of birth and/or citizenship to be able to disaggregate by migratory status. See the stepwise approach for data disaggregation below.

- For any migration-specific data collection, include relevant questions on sex, age and other variables to disaggregate migration data by these.

Points partly based on the Handbook on Measuring International Migration Through Population Censuses (UN DESA Statistics Division, 2017b).

Step 1: Disaggregation by migratory status can be defined by one of the following two variables:

- Country of birth: foreign-born and native-born population

- Country of citizenship: foreigners (including stateless persons) and citizens

Note: bear in mind that country of birth/origin and country of citizenship/nationality may not coincide.

Step 2: If there is a need to distinguish between migrants and their descendants, then migratory status can be defined by country of birth of the person and country of birth of the parents: foreign-born persons; native-born persons with both parents born abroad; and native-born persons with at least one parent born in the country.

Step 3: Other disaggregation dimensions. Countries interested in other migration-related population groups could further disaggregate the data by country of birth of the parents, duration of stay in country, and reason for migration. Internal migrants and internally displaced persons could also be considered if countries are interested in population mobility within the country.

UN DESA Statistics Division, 2018. See also IOM, 2021.

Various United Nations agencies have also developed guidance that is specific to different areas of migration data.

- United Nations Expert Group on Migration Statistics, Draft Report on Conceptual frameworks and Concepts and Definitions on International Migration, 2020. Background document prepared for Statistical Commission 52nd Session, March 2021.

- UN DESA Statistics Division, Handbook on Measuring Migration Through Population Censuses, 2017.

- Mosler Vidal, E., Leave no one behind. Migrants in the SDGs: A Guide to Data Disaggregation, 2021.

- Tomas, P.A.S., L.H. Summers and M. Clemens, Migrants Count: Five Steps Toward Better Data, 2009. Report of the Commission on International Migration Data for Development Research and Policy.

- Jeffers, K., J. Tjaden and F. Laczko, A Pilot Study on Disaggregating SDG Indicators by Migratory Status, 2018.

- International Forum on Migration Statistics (website). Showcases and brings together a number of presentations and materials about migration data.

- Migration Data Portal's resources section.

Provides an up-to-date view of migration data guidance and tools for practitioners. - There are also guidelines for improving data on various themes. Please see the thematic chapters for these.

There are various initiatives and organizations at the regional level that aim to improve the evidence base on migration. They will often provide guidelines for data collection and coordinate with organizations at the national level (such as national statistics offices [NSOs]). Such organizations are not in place in all regions. However, there have been initiatives to strive for similar harmonization of data collection in order to facilitate comparability across countries and produce regional data sets.

Guidelines for the Harmonization of Migration Data Management in the ECOWAS Region (2018) are a good example of joint efforts to improve harmonization of data at the regional level. These guidelines were prepared by the Global Migration Data Analysis Centre for the International Organization for Migration (IOM GMDAC), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), the European Union and the Economic Community for West African States (ECOWAS). The process involved extensive close coordination with ECOWAS Member States to discuss migration data practices and needs, so that the recommendations in the guidance could be most effectively put to use by national authorities. The continued involvement of and review by Member States ensure that the guidelines are tailored to the ECOWAS context and help pave the ground for concrete future joint work on migration data.

La mayoría de los datos sobre la migración proceden de fuentes nacionales. Algunas organizaciones internacionales y regionales también recopilan ese tipo de datos, y a menudo compilan datos nacionales para crear conjuntos de datos y recursos que permitan la comparación internacional. En este tema se ofrece información acerca de algunas de las principales fuentes de datos sobre la migración a nivel nacional, regional e internacional, centrando la atención en dos categorías generales: las tradicionales y las innovadoras. Para complementar el examen de las fuentes, se ha incluido una nota sobre las principales lagunas de datos.

National and subnational sources

Traditional sources of migration data at the national level can broadly be divided into two categories: statistical and administrative. Statistical sources collect data deliberately for the creation of official statistics and include censuses and surveys. Administrative sources collect data predominantly to support a country’s administrative processes, and include registers, border data collection systems and visa data.

Data can also be collected at the subnational level, in cities or wider administrative units (such as state, province, or other unit). Data from these sources are, to varying degrees, collated, cleaned, edited, aggregated and used to produce statistics. Official data and statistics on migration are often made available on the websites of national statistics offices, national ministries of the interior, ministries of employment and others.

The table below summarizes major traditional migration data sources. For further information on sources for different policy areas, see the Topic: Key sources of data, research and analysis in each of the thematic chapters of EMM2.0.

STATISTICAL SOURCES

| TYPE | ADVANTAGES | LIMITATIONS |

|---|---|---|

|

POPULATION CENSUSES |

|

|

|

HOUSEHOLD SURVEYS (including multipurpose household surveys such as labour force surveys, and specialized migration surveys). |

|

|

SELECTED ADMINISTRATIVE SOURCES

| TYPE | ADVANTAGES | LIMITATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| VISAS, RESIDENCE & OTHER PERMITS ISSUED |

|

|

|

POPULATION OR MIGRANT/OTHER REGISTERS |

|

|

| BORDER DATA COLLECTION SYSTEM |

|

|

Based on Hoffmann and Lawrence, 1996; UN DESA Statistics Division, 2017a; Eurostat, 2018; IOM Migration Data Portal, n.d.

Some countries have conducted panel surveys to collect more data on various aspects of migration. These include the New Immigrant Survey (NIS) in the United States of America, the Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB) in Canada and the Characteristics of Recent Migrants Survey (CORMS) in Australia.

- IOM Global Migration Data and Analysis Centre (GMDAC)

Aims to strengthen the role of data in global migration governance, support IOM Member States’ capacities to collect, analyse and use migration data, and promote evidence-based policies by compiling, sharing and analysing data from IOM and other sources. GMDAC was set up to respond to calls for better international migration data and analysis and works across knowledge management, capacity-building, and data collection and analysis. See, in particular, the GMDAC Migration Data Portal's dashboards for national data, for comparing indicators in a given country or region, or for comparing countries or regions. - Singleton, A., International Migration Statistics: Meeting the international recommendations – Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) Training Kit, 2009.

Discusses the identification of sources and their mapping in an inventory as well as the questions to ask from different types of sources (pp.7–13).

It is often possible to collate, compile or manage national data coming from a range of sources. With the right technology some national data systems can link, for instance, data from population censuses with those from surveys or administrative systems. This integration of data can produce comparable cross-national datasets that meet the criteria of the United Nations recommendations. However, in practice many countries do not effectively collate or share migration data that are collected across different areas of government.

International and regional sources

Several United Nations agencies, along with other international organizations, collect, use and/or analyse and disseminate migration data and other relevant data on specific topics.

| ORGANIZATION | TYPE OF DATA |

|---|---|

| UNSD/UN DESA |

Collects and disseminates migration statistics of countries, including on migrant stocks and flows |

|

IOM |

Collects, produces and analyses data on a wide range of topics (see box below for examples of IOM data sources) Created the global Migration Data Portal, a comprehensive and timely access point to migration statistics and information, and the Displacement Tracking Matrix, a system to track and monitor natural and human-induced disaster displacement and population mobility |

| UNHCR |

Collects, compiles, analyses and disseminates data on asylum seekers, refugees and selected related topics |

| ILO | Collects, compiles, analyses and disseminates data on labour migration, migrant workers and other selected topics |

| UNESCO | Compiles, analyses and disseminates data on international students |

| OECD |

Compiles, analyses and disseminates data on selected migration topics in OECD countries, including flows, labour market, integration policies and indicators, and migration and development Created an extended database for non-OECD countries on a range of topics (demographic characteristics, labour market outcomes, duration of stay and place of birth, among others) |

| WORLD BANK (predominantly through KNOMAD) | Collects, compiles, analyses and disseminates data on selected topics related to migration and development, including on remittances and recruitment costs |

| UNICEF | Compiles and disseminates data on child migration |

Note: This table is not exhaustive.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) collects and shares migration data across many topics for (and in the course of) its operations and for research.

Migration governance: Through projects such as the Migration Governance Indicators (MGI), IOM collects qualitative data on migration governance in a number of countries. Data:

- Reports

- Data by indicator (not publicly accessible)

Missing migrants: Under the Missing Migrants Project, IOM GMDAC collects data on migrants who have passed away or gone missing on migratory routes worldwide. Data:

Internally displaced persons (IDPs): The IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) collects data on internal displacement in various countries. Data:

Sources for other thematic areas on which IOM collects data are included in thematic chapters.

In addition to the above, IOM or researchers on behalf of IOM collect both qualitative and quantitative data on a range of topics related to migration, with findings published in various reports. IOM annual reports also contain valuable data and information on IOM operational activities.

Regional organizations can also collect and analyse data. See the box below for a non-exhaustive list of examples of this.

- Eurostat was established in 1953 and is the statistical office for the European Union. It shares various concepts and guidelines for data collection for European Union countries. Based on data supplied by members of the European Statistical System, Eurostat disseminates more than 250 tables of European Union statistics relevant to migration including on population, demography and migration, population projections, asylum, residence permits, and other topics.

- The Continuous Reporting System on International Migration in the Americas, (SICREMI, for its acronym in Spanish) produces biannual reports collecting migration data from diverse sources (such as censuses, surveys and administrative records) in countries in the region.

- The Mixed Migration Centre, formerly known as the Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS), provides largely qualitative data on irregular migration trends on a regular basis, especially in East Africa and the Horn of Africa. In addition to monthly summaries by country, the centre publishes thematic reports.

Further examples of resources per region are available in the Migration Data Portal, along with regional data overviews for different regions, and/or overviews of key regional statistics:

- Siegel, M., Where to find migration data, 2020 (video).

Because of rapid technological advancements, an increasing amount of migration-related information is now available from innovative sources such as big data.

Big data are usually understood as data generated automatically by users of mobile phones, social media, online payment services and other internet platforms and applications, as well as via digital sensors and meters. Such data are stored in real time in large databases, usually owned by private companies such as mobile phone operators, providers of social media platforms or other internet-based services.

Hilbert, 2013.

Letouzé (2015) distinguishes between big data as data (which are the “digital translation of human actions, interactions and transactions picked up by digital devices and services”) and big data as focused on the collection and analysis of such data (“an ecosystem of data, human and technical capacities and communities” producing and using such information for decision-making).

To understand big data, it is helpful to keep in mind:

- Big data are not only “big” because of their volume: the speed (“velocity”) at which they are generated and the complexity (“variety”) of the information are also considered as distinguishing features of this kind of data (Hilbert, 2013).

- They are different from data based on traditional sources, such as household surveys, as they do not refer to a random sample of individuals but to the totality of the population using, for instance, mobile phones or internet-based platforms, and these data are accessible in real time (Hilbert, 2016).

- Big data also differ from traditional data because of the specific technical and analytical methods required to extract meaningful insights from them and transform these data into ”value” (De Mauro, Greco and Grimaldi, 2016). Indeed, fields like data science are emerging to explore this. Meanwhile, automated data collection methods improve, the capacity to process big data increases and the ability to draw on artificial intelligence grows, enabling the identification of complex patterns, including by training machines to do so.

With about 5.1 billion unique mobile users, and around 4 billion active internet users around the world (Kemp, 2018), such “digital traces” present an opportunity to improve knowledge of various aspects of migration. The unprecedented amount of data being produced and the innovations in their analysis enable cross-checking and complementing data sources in order to achieve a more complete picture of migratory dynamics. It can also fill data gaps, particularly in knowledge of short-term movements. This is all the more relevant in light of current data gaps and the need to monitor progress towards migration-related targets in SDGs.

A growing body of research attempts to present the various ways in which big data can help elucidate, for instance, migrant flows, displacement, transnational networks or remittance flows (see Bengtsson et al., 2011; State et al., 2014). See Visa policy, categories and application management (particularly Sound policy principles applicable to the outsourcing of visa processing) and in Data collection and research on smuggling of migrants, for examples of how social media can be of use in some of those fields. Data innovation can help to better understand large phenomena quickly, as in health pandemics with cross-border implications such as COVID-19 (Rango and Borgnäs, 2020).

- Nielsen, Big data and international migration, 2014. This post in the United Nations Global Pulse blog discusses the use of big data for improving the evidence base on international migration.

- Data Innovation Directory. The Data Innovation Directory (DID) offers examples of uses of new data sources and methodologies in the field of migration and human mobility.

- IOM GMDAC and the European Commission’s Knowledge Centre on Migration and Demography (KCMD), Big Data for Migration Alliance (BD4M). Launched in 2018, it aims to harness the potential of big data sources for migration analysis and policymaking, while addressing issues of confidentiality, security and the ethical use of data.

- Spyratos, S., et al., Quantifying international human mobility patterns using Facebook network data, 2019.

The potential use of these innovative sources for policymaking, however, comes with significant challenges, as outlined in the box below. Indeed, it is yet to be seen exactly how useful big data will be for measuring international migration.

In the United Nations Global Pulse blog, a discussion on the potential of big data as a resource for understanding international migration outlines the following limitations to big data (text taken directly from the blog):

- Lack of ground truth data: as reliable traditional data on international migration flows are scarce, it is very difficult to test the applicability of a new data source as proxy;

- Lack of big data sharing/access: Private sector companies that hold much of these data are not incentivized and/or don’t have the mechanisms in place to make them available for analysis through open data protocols, “data philanthropy” partnerships, or other means;

- Big data privacy issues: These data, if not anonymized and properly aggregated, carry the risks of re-identification and use of personal information;

- Selection bias: Most big data sources are limited to online data users, generally biased towards younger, wealthier and more urban citizens;

- Complexity of big data modelling: By their very nature as newer, larger and more complex, these datasets require more advanced analytical techniques.

Nielsen, 2014 [text modified for clarity].

A number of organizations and initiatives collect, produce and/or analyse data on migration that can also be useful for policymaking:

- Research projects. Academic and other larger research projects can generate qualitative and quantitative data from in-depth studies. These are usually presented in reports, policy briefs, academic articles, background papers and other research material, although in some cases data sets may be made available. (See, for instance, the MIGNEX project.)

- Non-governmental organizations. NGOs often collect and share data related to their activities, or on migration topics they work on. These data are sometimes made accessible through reports published on NGO websites.

The availability and accessibility of some migration data has increased (Espey, 2017). However, there are still considerable gaps. The report of the Secretary-General to the 2019 Statistical Commission states:

Despite the unprecedented needs, statistics on international migration remain sparse. Basic statistics on migrant stocks and flows are lacking in many countries. For instance, … statistics on migrant stocks since 2005 are only available for 125 countries. Migrant stock data disaggregated by additional characteristics such as sex, age, country of origin and education are available in even fewer countries. Data on migration flows are even scarcer. Data on the size of emigration flows and stocks and their characteristics, are almost non-existent. As part of data collection from national statistics offices for the Demographic Yearbook of the Statistics Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the Secretariat, only 49 countries and areas have provided data on migration flows at least once since 2011 for at least one migration table.

United Nations Secretary-General, 2019; emphasis added.

Indeed, under the United Nations World Population and Housing Census Programme, most countries in the world conduct a census regularly, that is, once in ten years. Most countries also include a minimum of migration questions such as country of birth or citizenship in their census questionnaire. However, such information is often not tabulated, nor disseminated openly, resulting in a paucity of accessible migration data. It is generally accepted that this scarcity is a problem at global, regional and national levels and that a tremendous effort is still required to meet the existing data needs.

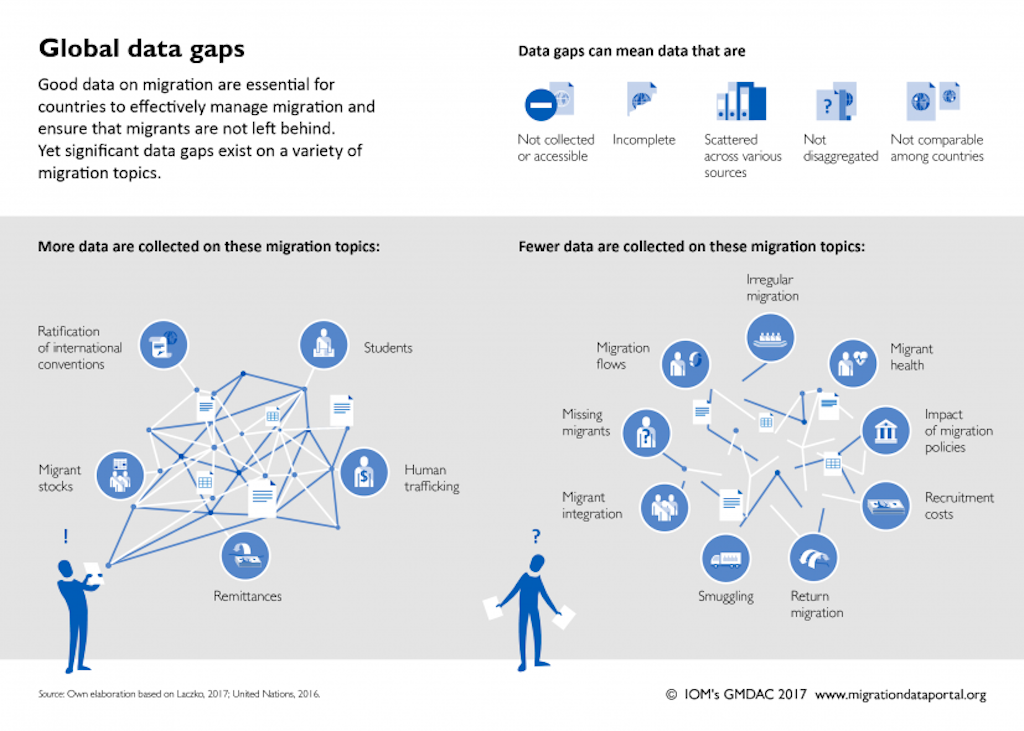

A data gap can mean that:

- data are not collected

- the coverage is incomplete

- data are scattered across different sources

- there are only total numbers and no disaggregation

- data are not comparable within or between countries

Data gaps can exist for specific policy areas (see, for instance, Data collection, analysis and research on migrants smuggling and Data landscape concerning trafficking in persons) and/or for particular migrant subgroups. Among the latter are people not included in civil registration systems (especially children whose births are not registered), migrant children who become effectively stateless en route and other vulnerable groups, such as gender non-conforming adults and children (for details, see Key sources of data, research and analysis in Gender and migration, Child migration and Migrants vulnerable to trafficking, exploitation and associated forms of abuse). It is important to note that migrants in an irregular situation will generally not be counted using traditional data collection tools, while stateless people may also be excluded at times or harder to identify. Moreover, identification issues can also impede accurate data collection concerning migrant deaths (Migration Data Portal, 2021e). Certain contexts, such as displacement in a context of crisis, can pose added challenges, such as data collection capacity becoming overwhelmed (more details in Key sources of data, research and analysis in Mobility dimensions of crises Prevention, preparedness and reducing risk, Emergency response and Recovery and Solutions). Overall, there is an urgent need for migration data that are disaggregated by age, sex and other variables, as well as for data from across policy sectors that are disaggregated by migratory status. Such information is needed in order to improve response strategies to challenges posed by migration, as well as to provide effective support and assistance to affected populations, especially vulnerable groups.

- Project Promoting Comparative Quantitative Research in the Field of Migration and Integration in Europe (PROMINSTAT): Funded by the European Union, the project researched the data available for all 29 European countries, focusing on stocks, flows, integration and discrimination.

- Poulain, M., N. Perrin and A. Singleton, Project Towards Harmonised European Statistics on International Migration (THESIM): This project compiled comparable statistical sources on international migration and asylum in the Member States of the European Union. Although results are from 2006, it makes available comprehensive information on the systems which produce migration statistics for Member States of the European Union.

Working effectively with migration data includes facilitating the timely collection of quality data and ensuring data are shared, analysed, used and/or communicated adequately at the relevant step of the policy cycle (see Table 1 in Role of data, research and analysis in the policy cycle, in this chapter). Each stage of data collection and processing will need different considerations in different contexts. For example, busy policy officers who need to brief senior colleagues do not need to have access to a full tabulation of census data. However, they do need to have the contact details for the person who works with those tabulations and can provide an analysis and answer questions about the data.

In all cases, stakeholders can take proactive steps to ensure that migration data are collected and used as effectively as possible and have the most impact on policy.

Ahead of collecting data, identify:

- The relevant policy information needs;

- The “population of interest”, and variables such as sex, age, migratory status and other key characteristics to later disaggregate;

- The relevant sources of data;

- Stakeholders interested in relevant data and analysis, and their needs, including in different government ministries and units, media, civil society, and more;

- The frequency and focus of reporting and/or analysis required, including different reports for different functions and audiences;

- The correct people to carry out (a) data collection and necessary cleaning of data, (b) data analysis and further research, and (c) reporting and communication;

- Steps to form an action plan to collect, process, analyse, report and communicate data for the identified policy needs (see How to develop data capacity to meet policy needs, below);

- Mechanisms to allow for feedback from data users to improve data activities.

During the different stages of migration data collection and management, further considerations are important, as laid out in Table 4.

| STAGE | CONSIDERATION | WHY? |

|---|---|---|

| DATA COLLECTION, PROCESSING AND STORAGE |

Follow and document all relevant data collection and processing protocols |

This will allow the collection and processing of data to be tracked. Following and showing compliance with designated protocols, including in particular those relevant to data protection, enables this. Such tracking allows stakeholders to identify where the data came from and assess how the data was processed, which assures the reliability of the data. |

| DATA MANAGEMENT - ANALYSIS, REPORTING, DISSEMINATION & USE | Ensure that data are shared with all relevant government ministries/agencies and collated centrally as appropriate | This will ensure reports are relevant for policymaking while benefitting from a solid understanding of the evidence base. |

| Ensure that data reporting and analysis are driven by policy needs | This will ensure that the reported and analysed migration data are the most relevant for specific migration policy topics. | |

| Ensure data and analysis are reported in ways that are tailored to different stakeholders | To ensure that information is communicated in formats and via platforms that best respond to the needs of policymakers and/or the public, specific strategies may be needed, such as shorter documents or presentations using simple language that signpost more in-depth analysis and research. Online reports, policy briefs, tweets, SMS messages and email alerts are different ways to reach policymakers and the public with information. | |

|

Ensure relevant metadata is available when publishing data. This should include information on: - the type and source of data, and details of any concepts and definitions used - data collection methodologies, including frequency - any weaknesses or gaps in methodologies - actors involved in data collection - where to find relevant reports |

Metadata is essential to allow for the correct interpretation and analysis of data. Often in migration, in the absence of official statistics, data (or unprocessed “raw” data) are used in calculations to produce estimates and indicators. It is important to understand the strengths and limitations of data which have not been processed using statistical methods. |

Note: This list is not exhaustive.

Data protection in migration needs to be considered at every stage of policymaking to ensure respect for the right to privacy and the protection of personal data of migrants. The collection and management of migration data can pose challenges related to data loss, data tampering and unauthorized access or unnecessary exchange of personal data. With the increase in personal data of migrants available, its protection warrants special consideration.

are any information relating to an identified or identifiable data subject that are recorded by electronic means or on paper.

IOM, 2011.

are individuals that can be directly or indirectly identified by the reference to a specific factor or factors. Such factors may include a name, an identification number, material circumstances and physical, mental, cultural, and economic or social characteristics.

IOM, 2011.

Protecting personal data is important to safeguard the right to privacy, which is a fundamental human right. Improper use and unauthorized disclosure of personal data may result in a variety of risks to the migrant, including verbal and physical violence, targeting as well as discrimination. There is a need to respect the right to privacy of migrants and to ensure that their personal data remain confidential.

Data protection is necessary for the safe exchange, secure storage and confidential treatment of personal data. These measures are especially important when collecting personal data of vulnerable populations in any context. In situations where there is conflict, displacement and/or forced migration, migrants may find their safety is further compromised if personal data are collected by, or shared with, governments without their knowledge and prior consent. (Further details on safeguards on data collection and processing in such contexts in Emergency response.)

States should aim to respect the privacy of data subjects, protect the integrity and confidentiality of personal data and prevent unnecessary or unwanted disclosure of personal data to third parties. To that end, they should:

- Establish a comprehensive data protection framework that meets national and international data protection standards. Include in the framework robust data protection laws and an independent data protection authority.

- Pay special attention to personal data of vulnerable migrants, ensuring such data are processed for a legitimate and specified purpose and in a lawful, fair and transparent manner while providing anonymity and confidentiality as appropriate.

- Ensure that only the minimum data necessary are shared with third parties.

- Ensure that the risks of sharing personal data do not outweigh the benefits.

- Use secure systems to facilitate data sharing between relevant actors.

- Establish data protection safeguards to provide anonymity and confidentiality of personal data.

- Designate focal points in the relevant agencies and organizations for establishing a governance structure/framework for data sharing, managing potentially divergent interests and monitoring ongoing use of data.

- Develop a common data management system and/or standards detailing who will use the system, who will administer it, what software and technology will be required, and what security will be put in place to protect data.

Good policy and practice measures to ensure that data are not shared where there are protection risks include:

- Establishing appropriate measures, such as: clear access controls; detailed logs on who processes data and when; and firewalls to ensure that data that are collected for a particular purpose are not used for other purposes.

- Ensuring that both State and non-State actors who are in possession of data understand their legal and ethical responsibilities.

The Canadian province of Manitoba takes the following strategy when presenting data on immigration: all values are rounded up to the closest multiple of 5. This approach is meant to prevent the possibility of identifying individuals when IRCC data are compiled and compared to other publicly available statistics. Numbers below 5 are simply shown as “–“ for the same reason.

Province of Manitoba, 2018.

Data protection instruments at international, regional, national and local levels are based on the right to privacy, enshrined in Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

| GLOBAL INSTRUMENTS |

|

|---|

Note: This list is not exhaustive.

| REGIONAL INSTRUMENTS |

|

|---|

Note: This list is not exhaustive.

The Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (Convention 108) was the first multilateral agreement on personal data protection, adopted in 1981. Although developed by the Council of Europe, any State can become a party to Convention 108. The updated Convention 108+ with improvements in relation to the previous text is currently in the process of ratification by Member States.

In May 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) entered into force to manage data protection and privacy in the European Union and the European Economic Area, while also addressing transfer of personal data outside Europe. The evaluation report on the GDPR published in June 2020 showcased the importance of strengthened data protection safeguards to protect individual rights, increasing transparency and accountability.

International organizations supporting States in their migration management and/or humanitarian assistance also have their own set of data protection principles.

- Martens, R., Data Protection Manual, 2010. Based on IOM Data Protection Principles, this manual guides IOM staff and other operating organizations in processing personal data to protect beneficiaries’ rights.

- United Nations, Principles on Personal Data Protection and Privacy Principles, 2018. Provides guidance to United Nations system organizations on protection of personal data.

To develop the capacities of relevant stakeholders to improve collection and use of migration data, designing a national action plan can be very helpful. Efforts to build migration data capacity can be an effective approach to meet data needs over the longer term. Like other capacity-building activities, this requires, time, resources, collaboration among stakeholders (for instance, NSOs and ministries) and political commitment. Before embarking on any migration data activity, it is useful to consider the proactive steps outlined in Key considerations at different stages of data collection and processing on using migration data for policy.

Elements of a national action plan could include:

- Mapping the country’s migration data sources, identifying all possible sources including unexploited data which are collected but not always used (such as administrative data);

- Harmonizing migration data collection and management methodologies with international standards. This could include developing guidance on harmonized practices in the collection, analysis and dissemination of national migration data;

- Developing and promoting the use of common migration modules for censuses and surveys;

- Carrying out migration data training activities and workshops on an ongoing basis, with training materials that fit local needs while following international guidelines;

- Developing or updating existing national Migration Profiles;

- Establishing national migration data Focal Points – such as representatives from national statistics offices, other ministries and government agencies, and non-governmental partners – to coordinate on national migration data;

- Creating a technical working group on migration data with the migration data Focal Points;

- Making census microdata available to analysts and engaging external experts to develop census data analysis tools;

- Assessing and evaluating all relevant activities to improve practice on an ongoing basis.

While usually focused on the national level, action plans can also improve data capacity at the regional level, which can in turn greatly benefit countries.

Elements of a regional migration data action plan could include:

- Organizing regional workshops for countries to share experiences and best practices;

- Through a network of national Focal Points, establishing regional technical working groups to coordinate regional activities on migration data, including efforts to harmonize data;

- Developing regional Migration Profile reports;

- Creating a regional-level mapping or inventory of migration data sources;

- Undertaking joint or regional-level resource mobilization action for migration data, including resourcing around digital technologies.

Data capacity-building initiatives developed by regional or international organizations for States may involve developing technical documents, holding training workshops or offering specialized technical assistance on particular data tasks. In practice, it can be most effective to use a combination of these efforts to build and/or develop migration data capacity (IOM GMDAC, 2019). The UNSD developed a toolkit to assess national migration data capacity (see To go further below).

The ECOWAS regional guidelines mentioned previously are an example of migration data capacity-building resources.

- UNSD: This toolkit on assessing national migration data capacity includes a set of questions to assess the capacity to produce reliable, timely and comparable statistics on international migration, in order to identify where capacity-building is needed.

- IOM: Through its Global Migration Data Analysis Centre, IOM supports governments through migration data capacity-building. This includes delivering migration data training workshops, developing relevant specialized tools and manuals on migration data, sharing and explaining data available in the Migration Data Portal, showcasing good practices, including on capacity-building, and more. For more information see their website.

- UNDESA is involved in a variety of ways in improving the global evidence base on migration, including through capacity-building on data. For more information see their website.

- The ILO offers training courses and seminars as well as online training tools on specific topics to support the implementation of international labour statistics standards. These are available in English, French and Spanish. For more information see their website.

- World Bank: The Statistical Development and Partnership Team of the Development Data Group works to improve statistics that support the Bank’s mission to fight poverty. For more information see the website.

Further, international migration survey programmes can assist national statistical offices by developing questionnaires and manuals, preparing software and seconding migration experts. Survey programmes can be carried out by a consortium of research institutes.

- Latin American Migration Project: A multidisciplinary research project systematically collecting data on migration to the United States from 10 Latin American countries through household surveys (expanding the Mexican Migration Project).

- Households International Migration Surveys in Mediterranean Countries (MED-HIMS): This project is a joint initiative of the European Commission, World Bank, UNFPA, UNHCR, ILO, IOM and League of Arab States. With the first results published in 2016, it aims to “collect representative multilevel, retrospective and comparative data on the characteristics and behaviour of migrants and the consequences of international migration”.

- Migration between Africa and Europe Project (MAFE): An independent research initiative focused on the two-way movement between Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe to understand patterns and determinants of migration and glean information on the impacts of migration on development in order to leverage these benefits in different policy areas. It ran from 2005 to 2012 (Final report).

- Los datos son la piedra angular de la elaboración de políticas migratorias basadas en información contrastada. Los datos se reúnen en su mayor parte a nivel nacional, y son esenciales en las etapas de determinación del asunto, formulación, implementación y evaluación del ciclo de políticas.

- Los marcos y compromisos mundiales, como la Agenda 2030 y el Pacto Mundial para la Migración, ponen de relieve la importancia de los datos sobre la migración y la urgente necesidad de mejorarlos.

- La base de información comprobada sobre la migración es fragmentaria; en particular, no existen suficientes datos de buena calidad, oportunos y comparables sobre la migración. Hay lagunas en muchos aspectos importantes de la migración, y faltan también datos desglosados según la situación migratoria en los diferentes sectores. Además, los países utilizan a menudo conceptos y definiciones diferentes al recopilar los datos, lo que dificulta mucho la comparación.

- Las nuevas tecnologías y metodologías han contribuido a un aumento sin precedentes de la cantidad de datos relacionados con la migración disponibles y de las posibilidades de procesarlos. Aunque aún no está claro en qué medida los nuevos tipos de datos, como los macrodatos, podrán utilizarse sistemáticamente para mejorar la base de información comprobada sobre la migración en apoyo de la elaboración de políticas, hay avances prometedores.

- La comprensión de los conceptos fundamentales de los datos migratorios (por ejemplo, de la diferencia entre las poblaciones y los flujos), así como de los puntos fuertes y las limitaciones de diferentes tipos de fuentes de datos, es indispensable para el uso acertado de esos datos en las distintas etapas del ciclo de políticas.

- Para realizar un trabajo efectivo con los datos sobre la migración a nivel nacional, puede ser útil elaborar un plan de acción sistemático destinado a recopilar, procesar, analizar y comunicar datos que respondan a las necesidades señaladas, y movilizar a los asociados necesarios para la implementación satisfactoria y eficaz de ese plan.

- Hay muchos tipos diferentes de actividades de fomento de la capacidad que pueden ayudar a mejorar la recopilación y el uso de datos sobre la migración.