- Carling, J., How Does Migration Arise?, 2017.

This report presents a complementary way of assessing drivers, focusing on aspirations and migration infrastructure rather than root causes.

This section discusses the drivers of international migration, including those in both countries of origin and countries of destination. It also discusses barriers to migration; factors that tend to hinder movements that might otherwise occur. The section argues that migration is likely to increase, as long as current drivers persist. It concludes, however, that the scale of migration should remain manageable in the years ahead if countries of origin and destination cooperate in managing migration.

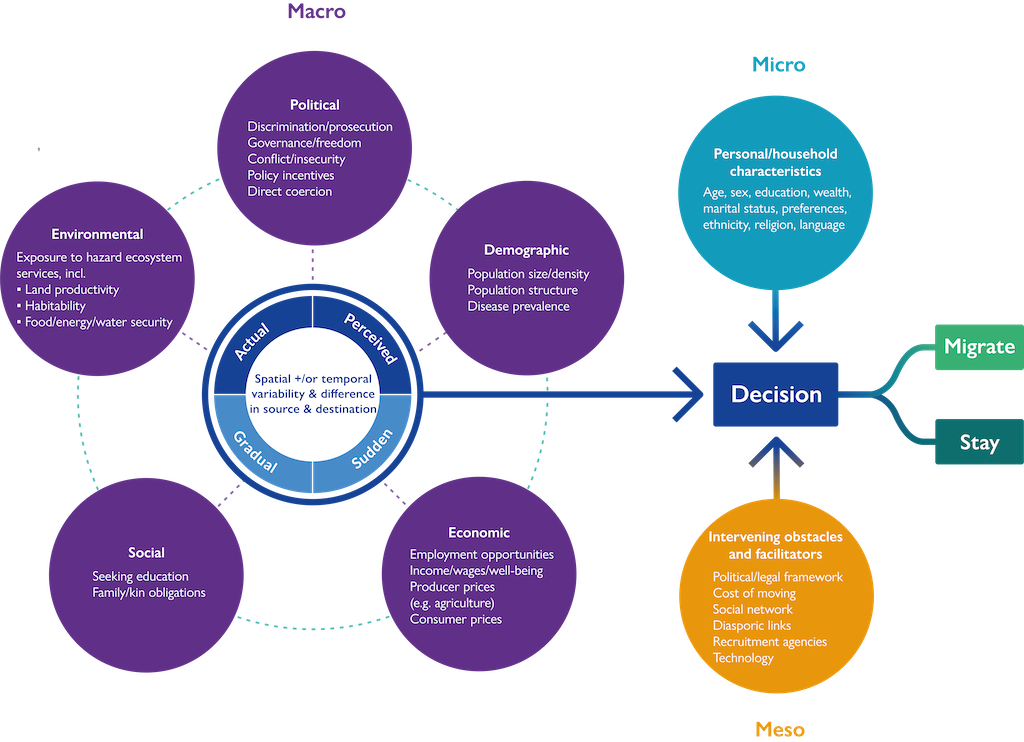

Figure 8 visualizes how the various drivers and facilitators of migration, as well as barriers to migration, interact (Foresight, 2011). There are five primary macrolevel drivers of migration – economics, demographics, social, political and environmental. These provide the broad context in which people move from one location to another. In addition, there are microlevel factors (such as age, gender and income level) that determine how the macro factors influence migration decisions at the personal or household (micro) level. Finally, there are intervening factors that facilitate or impede migration (mesolevel factors), including the human, financial, physical and psychological benefits and costs of moving, and the emigration and immigration policies that make some forms of migration easier and others harder. The interplay among these three sets of drivers determines how many people will migrate, from which communities of origin, to which destinations, with what modes of attempted entry, and with what type of welcome.

Based on Foresight, 2011.

The brief discussion below focuses on the ways in which current drivers occur and their impact on likely future movements of people across international borders.

Classical macroeconomic theory argues that the difference in income between origin and destination communities and countries is one of the main reasons that people migrate. Newer economic theories add that households use migration to reduce economic risk by diversifying their sources of income. For example:

- Some members of the household remain at home, engaging in subsistence agriculture, while others move to urban areas to engage in wage employment.

- Other members of the household may migrate internationally to gain even higher wages and ensure that the household is protected against local or national economic crises.

- Remittances from those earning more to those with fewer options help equalize income within the household.

Further economic theory argues that the global economy itself makes it likely that people will migrate from from lower-income countries with a less skilled workforce, to wealthier countries with a more skilled workforce. As the education level rises in wealthy countries, there are fewer native-born people willing to work at the wages and under the working conditions offered for less-skilled jobs. This provides opportunities for migrants to fill economic niches.

Economic differences between nation States are widening, increasing the motivation for economically motivated migration (World Bank, 2018). It should be noted, however, that the poorest of the poor seldom have the resources needed to migrate internationally; poor people from the least developed countries are more likely to move internally or to neighbouring countries that provide better economic opportunities, if at all.

Most migrants are young people seeking work. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), global participation of youth in the labour force has been declining since 1999 and the youth unemployment rate was 13.6 per cent in 2019 (ILO, 2020). It has been particularly high in Northern Africa (30 per cent in 2019) and the Arab States (23 per cent in 2019), well above the rest of the world (ILO, 2020). Young people are also more likely to be underemployed or in jobs that are highly vulnerable to frequent periods of unemployment.

International migration will also be affected by the future of work. Developments like the mechanization of agriculture, the growth of multinational companies that draw on a global workforce and the innovations that artificial intelligence is enabling will influence how people move, or do not move, for work. (Read more on these new trends in Labour migration).

Fertility rates and replacement migration

Population growth has slowed in many parts of the world. However, the momentum from past and present fertility rates means that the world’s population will continue to grow even as future fertility falls. Most of the world’s population is in middle-income countries (Population Reference Bureau, 2021). World fertility rates (that is, the number of children per woman) have dropped to 2.3 children per woman, but fertility in low-income countries remains high, at 4.7 children per woman (Population Reference Bureau, 2021). Fertility in higher-income countries is below replacement levels, at 1.5 (Population Reference Bureau, 2021). In high-income countries, population is expected to decline as societies age: the number of people aged 65 and over is projected to increase from 700 million in 2020 to 1.5 billion in 2050 (UN DESA Population Division, 2020b). Without immigration, these very different fertility patterns mean that the population shares of the world’s countries will change during the next decades.

La migration internationale qui serait nécessaire pour compenser la décroissance démographique, la diminution de la population en âge de travailler ainsi que le vieillissement mondial de la population.

Division de la population de l’UNDESA, 2001 : 1.

Le rapport de la Division de la population de l’UNDESA intitulé « Politiques démographiques mondiales 2019 » [en anglais] remarque que les moteurs de la démographie sont d’importants facteurs d’immigration. En effet, un tiers des pays mènent une politique d’immigration en réponse au vieillissement de la population et au déclin démographique à long terme (Division de la population de l’UNDESA, 2020b).

L’immigration peut, elle aussi, contribuer à faire face à la hausse de la demande de main-d’œuvre dans les pays à population vieillissante ou à faible croissance démographique. Le vieillissement de la population conduira, selon toute vraisemblance, à des pénuries de main-d’œuvre, surtout dans des secteurs inadaptés aux travailleurs plus âgés, et aura des répercussions sur les systèmes de sécurité sociale (Aubry, Burzynski et Docquier, 2016). La demande de main-d’œuvre dans le secteur des services à la personne, en particuliers les services destinés aux personnes âgées, devrait augmenter. Parmi ces professionnels figurent les gériatres, les infirmiers et infirmières, les aides-soignant(e)s à domicile et autre personnel soignant. Les immigrants représentent d’ores et déjà une proportion élevée de la main-d’œuvre dans ces secteurs. Face au vieillissement de la population, les gouvernements rencontreront sans doute davantage de difficultés à maintenir la base d’imposition nécessaire au financement des systèmes de retraite et de santé, déjà sous tension. La migration est considérée comme une partie de la réponse au problème de renouvellement de la main-d’œuvre et des personnes contribuant au système fiscal et cotisant au régime de la sécurité sociale. Un pays à population vieillissante dont les politiques limitent l’arrivée de main-d’œuvre extérieure devra probablement envisager de relever l’âge de la retraite et devra assumer les conséquences en résultant sur le plan sanitaire et en termes de bien-être social. Dans les pays d’origine, l’émigration de main-d’œuvre en âge de travailler peut contribuer à réduire la pression sur le marché du travail (Division de la population de l’UNDESA, 2020a).

Selon une enquête réalisée par les Nations Unies dans le cadre de sa publication « Politiques démographiques mondiales 2019 », un tiers des 111 gouvernements répondants ont déjà adopté des politiques d’immigration destinées à répondre au vieillissement de la population et à remédier au déclin démographique (Division de la population de l’UNDESA, 2020a).

- Population Reference Bureau, Fiche de données sur la population mondiale 2021, 2021 [en anglais].

- Division de la population du Département des affaires économiques et sociales des Nations (UNDESA), Politiques démographiques mondiales 2019, 2020b [en anglais]. L’édition 2020 de la publication bisannuelle est consacrée aux politiques et programmes relatifs à la migration internationale dans le monde.

- Population Pyramid est un projet d’études doctorales en sciences de l’informatique proposant des projections et des visualisations scientifiques sur le thème de la migration. La plateforme indique que d’ici 2050, la population dans les pays les moins avancés devrait atteindre près de 2 milliards de personnes (contre 1,07 milliard à ce jour), avec environ 30 % d’enfants de moins de 15 ans.

Différences liées au genre dans les schémas migratoires

Il existe des différences significatives et variables dans les schémas de migration des femmes, des filles, des hommes, des garçons et des personnes non binaires. Malheureusement, la collecte de données sur les différents genres est toujours profondément insuffisante, et les efforts pour combler ces lacunes de données sont variables selon les pays (OCDE, 2019). Les différences liées au genre s’intéressent aux femmes, aux filles, aux hommes, aux garçons et aux personnes non binaires. Cependant, certains aspects particuliers aux femmes valent la peine d’être mentionnés. Ainsi, un nombre croissant de femmes migrent, pour la plupart, afin d’occuper des postes dans des secteurs très genrés, notamment les services à domicile et les soins infirmiers. Alors que les obstacles à la migration dans les pays d’origine tendent à s’amenuiser pour les femmes et que les opportunités s’élargissent dans les pays de destination (et ne se limitent plus uniquement aux services de soins aux personnes âgées dans les pays à population vieillissante), un nombre encore plus important de femmes devrait franchir ce pas. De plus en plus, les femmes migrent de manière autonome ou en tant que principal soutien de famille. De même, l’évolution des attitudes envers les femmes, avec dans certains cas un renforcement de la violence à leur encontre, devient un facteur déclencheur de la migration féminine (Hallock, Soto et Fix, 2018). Pour en savoir plus, veuillez consulter le Genre et migration.

Emergence of new States

The past 50 years have seen a proliferation of new States and the attempted secession of breakaway regions. This has been caused largely by the break-up of countries such as the former Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, as well as by surging nationalism within subregions. These changes have often been accompanied by migration; in some cases, the change in borders make former citizens into non-nationals. And with more nations, there are more borders to cross. Considering only the United Nations member States, there were 193 generally recognized nation-states in 2020, up from 51 in 1945. People who had moved internally became international migrants even if they had arrived at their destination before the incorporation of new States occurred. Refugees, and displaced persons in particular, are the result of these processes. Too often, the formation of new States leads to the expulsion of those considered to be of another nationality or citizenship, particularly when these persons practice a different religion or have a different ethnicity from those in power. A growth in statelessness has also resulted from real and attempted changes in borders, with some persons having the citizenship of neither the State in which they resided nor the State of their origin.

Displacement due to conflict

Political instability, conflict and human rights violations are further causes of migration. Some of the displaced population may be defined as refugees (see Types of movement in the same chapter) while others are internally or internationally displaced without the legal protections afforded to refugees. In these cases, the governments of the countries of origin may be implicated in the actions that displace people. In other cases, non-State actors ranging from insurgent forces and terrorist organizations to family members may threaten the security of those who are displaced. The key to whether people are forced to flee lies in the extent to which governments have the capacity and will to intercede on behalf of potential victims and provide them with protection.

Political factors also determine the willingness of States to admit international migrants and allow them to remain, at least temporarily. Many countries have ratified United Nations human rights conventions that commit them to providing all persons with basic rights such as due process. As a result, in many countries, migrants without legal status can nevertheless stay several years by applying for various forms of relief from deportation. They may have been smuggled into a country, work in the underground economy, and apply for relief only when apprehended. Most developed countries extend eligibility for at least some basic services to all residents, regardless of legal status, making it easier for migrants to survive while trying to establish a foothold.

On the other hand, rising ethno-nationalist populism may influence the willingness of political leaders to admit international migrants, particularly but not exclusively if such migrants are perceived by the public to be in irregular status. Anti-immigration sentiments may be fuelled by social media, which too often spread misinformation about the realities of migration (McAuliffe, 2018). Such populism is a two-way street, though. Not only does it affect national policies – often leading to restrictions in immigration – but it also affects the interest and willingness of would-be migrants to move to a destination where anti-immigration rhetoric and actions predominate. As ethno-nationalist populism increases, higher-skilled immigrants with more options may be reluctant to come to a country where they feel unwelcome (Coughlan, 2018).

Environmental changes, particularly in the context of climate change, can have profound consequences on land, people, and migration. According to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), climate change is projected to increase the displacement of people over the course of the twenty-first century (2014).

There appear to be four principal pathways by which environmental drivers in general and climate change in particular affect migration patterns:

- Recurrent and persistent droughts that undermine livelihoods, especially in rural communities that rely on rain-fed agriculture. These combine with desertification, land degradation and habitat/ecosystem loss that also affect livelihoods.

- Rising sea levels and coastal erosion that over time make vast areas of land uninhabitable or undermine livelihoods such as agriculture.

- Acute disasters linked to natural hazards (only some of which are climate related) that appear more frequently and more intensely, such as earthquakes, floods, fires, tornadoes, tsunamis, and cyclones.

- Conflicts over scarce resources, most of which are within countries and can lead to political instability; communal, ethnic and religious divisions; and mass displacement of people.

The more detailed evidence reviewed by the IPCC suggests that “[e]xtreme weather events provide the most direct pathway from climate change to migration”, but in the longer term, “sea level rise, coastal erosion, and loss of agricultural productivity … will have a significant impact on migration flows” (Adger et al., 2014: 767; 768–69).

Pre-existing levels of resilience give some households greater capacity to cope with environmental drivers while making others more vulnerable. These levels of resilience can have different impacts. On the one hand, more resilient households may have greater ability to stay in their home and adapt to environmental change; on the other hand, resilience also gives people the financial, social and human resources needed to migrate. The most vulnerable will be affected worst, but they will also be the least able to migrate any distance from their homes.

Customs and social norms, as well as changes to them, are key drivers of migration. For instance:

- Cultural and societal roles may compel people to remain at home (despite their own wish to move) or give them the opportunity to go elsewhere.

- Policies and practices that discriminate or persecute based on social and cultural norms may trap people in place, or may force them to flee from harm’s way. For example, social and cultural attitudes towards sexual orientation, female labour force participation, female genital mutilation, and domestic violence can take away the means through which people can migrate or be important drivers of migration. These attitudes affect not only those directly targeted but also others who do not share the values that underpin the attitudes.

- As societies change, opportunities may arise for migration by choice rather than necessity. This can sometimes result from the social remittances that migrants send home in terms of new values and principles. For example, as women have gained greater autonomy, the potential to migrate for their own employment or education has grown significantly.

Also, social networks are one of the most important drivers of migration because they enable migrants to access information and resources needed to cross national borders, obtain employment and housing on arrival, and integrate into new communities.

Family formation and family reunification are important social drivers of migration, whether to a new home in the same or nearby community or thousands of miles away to a new country. In the case of family formation, a migrant moves to marry, or with the intent to marry or reside as a family unit with a resident (national or foreigner) in the country of destination. In family reunification, one spouse or parent migrates, and then brings other family members to join him or her.

Pursuit of education is another social driver of migration. Parents migrate in order to provide better educational opportunities for their children; young people migrate in order to enrol in institutions of higher education. In turn, education programmes targeting international students expand. Institutions strive to attract students, and their student fees, and to expand opportunities to collaborate with similar educational institutions across borders. In some cases, such migrants intend to migrate temporarily while pursuing studies; in other cases, education abroad leads to more permanent job opportunities or marriage in the destination country.

Relatively few of those affected by the macro drivers described above actually migrate, especially to other countries. Carling (2002) argues that those affected by such drivers can be divided into four distinct groups, based on whether they do or do not move, and whether they move voluntarily or not:

- Those who voluntarily move;

- Those who involuntarily move;

- Those who voluntarily remain at home;

- Those who involuntarily remain at home even though they might prefer to migrate.

Understanding migration requires analysis of the facilitators and barriers not only to movement but also to immobility.

Some of these facilitators and barriers to movement and immobility relate to household, family and individual characteristics of affected populations. Socioeconomic characteristics of families and individuals within those households are one of the most important of the micro drivers of international migration. The very poorest of the poor tend not to be as mobile as others, largely because they lack the capital needed to successfully relocate. They generally have few financial resources to undertake what is often an expensive enterprise; their human resources – generally measured in education and skills – are also inadequate or non-transferrable to a new location; and their social capital may be lacking if they do not have networks already abroad. Not all forms of capital induce migration, though. For example, land- or business-owning households may have little financial need for all or some members to migrate, or they may be reluctant to leave their property behind.

Even in situations of forced migration, socioeconomic characteristics may play a role in determining whether people will leave their home communities and where they go to find greater safety. Families measure the risks and benefits of staying in place against those of flight for each member. The risks vary depending on many personal factors – including gender, age, sexual orientation, health status, size and composition of the household – as well as the nature of the threat. The involuntarily immobile may be the most at risk but the least able to flee because of pre-existing vulnerabilities. They are trapped in place despite a desperate need to migrate. As this discussion indicates, it is a mistake to think of migration as either forced or voluntary, as there are often elements of both. The decision-making involved in migration is much more complex than that.

Other facilitators and barriers to migration and immobility are systemic, rather than tied to a household, a family and an individual. These factors also influence trends and patterns of movement. For example, the communication revolution helps potential migrants to learn about opportunities abroad, encouraging and enabling people to move over national borders. The most trusted information about opportunities abroad comes from migrants already in the destination, since they can inform family and friends at home in a context that both understand. Transportation innovations have also influenced migration patterns.

Recent discussions on the interconnections between migration and information and communication technologies have focused on the various ways that technology impacts aspects of migration (further details on considerations in the digital age, including on Migration narratives).

- International migration is multi-causal, involving macrolevel, microlevel and intervening factors.

- Drivers include economic, political, demographic, environmental, and sociocultural forces.

- Facilitators and barriers to migration are important in determining whether individuals and households are able to move to another country.